The dark side of Rosia Poieni, Europe’s second largest copper mine

Rosia Poieni, a copper giant on the edge of Europe

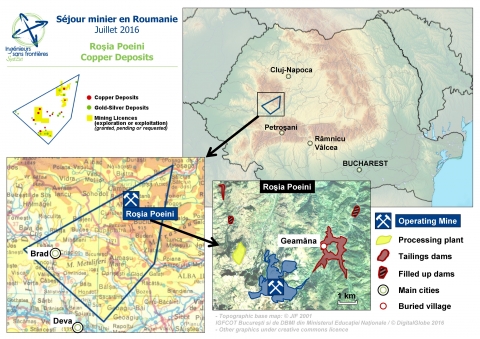

Located in the Apuseni Mountains in Western Romania, the Rosia Poieni mine contains the second largest deposit of copper found anywhere in Europe. Its metallic potential is huge: its deposits are thought to stand at more than one billion tonnes of ore with a grade of 0.36% copper and 0.25 g/t gold. This porphyry deposit is present in small clusters scattered throughout the rock and is primarily composed of copper and iron sulphates (chalcopyrite and pyrite, respectively).

Rosia Poeini open-pit mine | SystExt · July 2016 · cc by-sa-nc 3.0 fr

A recent mining history

Unlike many of its neighbouring gold mines, the story of the Rosia Poieni mine begins recently. The deposit was discovered as part of a huge scheme of prospecting programmes carried out in the 1960s. Open-cast mining began a decade later under the communist regime of Ceaușescu. Since 1983, the State-owned company Cupru Min has taken over its management and set up the current ore processing facilities.

Cupru Min headquarters in Abrud | SystExt · July 2016 · cc by-sa-nc 3.0 fr

The shadow of the IMF and the failure of privatisation

Considered a “black hole” for the country’s economy by the IMF, the government announced the privatisation of the Cupru Min company as part of an agreement with the organisation at the beginning of 2012. The Canadian company Roman Copper, specifically set up by an investment fund and with no mining-related experience, was chosen by Bucharest. But negotiations amounted to nothing: Roman Copper refused to pay a surety bond of €32 million for environmental protection in the area. The government has said it is “ready to revive proceedings” but nothing has happened since.

Rosia Poeini Mine: processing plant, workshops and offices | SystExt · July 2016 · cc by-sa-nc 3.0 fr

Constant activity

550 people currently work at the Rosia Poieni site (in the mine, plants and offices). Every day, 14,000 tonnes of rock are mined. Half of this is sent to the ore processing plant and the other half is simply dumped into the waste rock pile on the edge of the pit. Crushed down and chemically treated (specifically via the flotation method), the ore is concentrated into a powder containing 20% copper. It is this product that is then exported, mainly to China, where it is transformed into copper metal.

Rosia Poeini Mine, mining operations | SystExt · July 2016 · cc by-sa-nc 3.0 fr

Şesii, death valley

Since the mine opened in the 1980s, the operator has been dumping mining waste into the surrounding valleys. Now closed, an initial settling pond was built near to the village of Curmătură, with more than 300 families evicted from their homes to accommodate it. In 1986, the Cupru Min company set about discharging its mine tailings. These made their way towards the village of Geamăna where 1,000 people still lived. 30 years later, the Şesii valley has become a vast settling basin.

Satellite view of Rosia Poeini Mine and the Şesii Valley | Imagery ©2016 CNES / Astrium, Map data © 2016 Google, 07/09/2016

Geamăna: a village engulfed, its environment laid to waste

The Geamăna settling basin now covers an area of more than 130 hectares and is expanding by one centimetre every year. With no regard for the environment, more than 130 million tonnes of tailings have been discharged into it with 14,000 tonnes arriving every day. This acidic sludge contains various metals such as copper, iron, zinc, lead and even arsenic.

Geamăna, engulfed village in the settling basin | Kainet · April 2015 · cc by-nc 2.0

Pitiful wastewater processing

Before 1993, the discharge into the watercourses contained very few metals overall. But when it became too hard to sell the iron sulphates (for manufacturing sulfuric acid) as it had previously done, the plant set about discharging them into the watercourses. Ever since, the metals released and the acidity of the water have significantly increased. This phenomenon, called “acid mine drainage” is supposed to be counteracted by dumping huge quantities of lime into the lake and creating a treatment basin further downstream. In theory, such measures guarantee that waste water remains neutral and clean. Yet, a report by the French Geological Survey (BRGM) in the year 2000 found the water’s pH to be very acidic (2.7). The impact was measured over a distance of 5 km from the river Şesii to its confluence with the Arieş.

Geamăna, settling basin and lime supply | SystExt · July 2016 · cc by-sa-nc 3.0 fr

Recurring serious accidents

In September 2004, hundreds of cubic meters of contaminated water leaked from the settling basin with pollution recorded as far afield as Turda, some 80 km further downstream. In 2008, thousands of dead fish were seen floating on the Arieş river for three days as a result of Cupru Min forgetting to activate certain control devices. In 2011, after a pipe burst, hundreds of tonnes of mining waste were discharged and made their way into the Aries, etc. Every year, the local authorities impose fines on Cupru Min (€2,500 in 2004) but these are derisory compared to the damage caused and seemingly have no effect on the mining company’s behaviour.

Geamăna, settling basin | Sergiu Bacioiu · March 2013 · cc by-nc 2.0

Persistent pollution in the region

As noted by the BRGM in its report from the year 2000, “occurring at several different levels across the site, the acidification and movement of metals have a negative impact across the region on both underground and surface waters.” A 2004 study by Serban M. et al. found that the four main mines in the Arieş river basin (Rosia Montana, Rosia Poieni, Baia de Aries and Iara) have a direct and significant impact on the watercourses, underground waters and soil as well as on the flora and fauna.

Map of the Aries River's basin and main sources of mining pollution | Source : Michel Deshaie · 2009 in L’or controversé de Transylvanie

Urgent environmental considerations are needed

Cupru Min’s director guarantees that there is no pollution risk associated with his company’s mining operations. At the same time, the authorities keep quiet about any accidents and recurring incidents of pollution linked to this or any other corporation. Local associations struggle to make their voices heard about the severity of the damage inflicted on people’s health and the environment in this mining region. Against such a backdrop, it is hardly surprising that, on 21 July 2016, the European Court of Justice condemned Romania for breach of its obligations under Directive 2006/21/EU on the management of waste from extractive industries.

Geamăna, writing at the entrance of the settling basin "Don't forget Geamăna, save Roşia Montană" | SystExt · July 2016 · cc by-sa-nc 3.0 fr